The Dunlavin area 1881-1901.

Let us begin by looking at place. A parish priest once gave an accurate description of his domain when he wrote: “Geographically then, the parish of Dunlavin, entirely within West Wicklow, touches upon Hollywood, Ballymore-Eustace, Kilcullen and Narraghmore, and forms to a great extent and for many miles the North-Western boundary of Wicklow. We run along the frontier from Tober to Colbinstown station”. While this description is very accurate, it does not give us the full picture. The parish really may be quite neatly divided into two halves, upland and lowland.

The inland part of the parish, with the village of Donard acting as a lower order services centre, comprises the Donard- Davidstown- Glen of Imaal region. An idea of just how mountainous this area is can be got by a glance at a map which shows the boundaries of Dunlavin Roman Catholic parish. This side of the parish goes right up to the summit of Lugnaquilla itself. Despite this, however, the Wicklow mountains act as a barrier and the distant East Wicklow towns of Bray, Wicklow and Arklow have little bearing on life in West Wicklow. Apart from the obstacle of the Wicklow mountains, there is also the question of distance. Each town in the East of the county is forty or more miles away, and in the winter Wicklow’s climate is another factor which hinders communications between the East and West of the county. Snow and freezing conditions made the mountain route ways treacherous. The mountains themselves were also more exposed in the late 19th century than they are today, as the coniferous forests that dot the mountains nowadays are quite recent in origin.

Given that the physical division of Co. Wicklow into East and West exists even today, it is likely to have been much more pronounced in the study period of 1881 – 1901. While late 19th century people were probably a lot more mobile than we sometimes imagine, there is no doubt that inferior transport meant that the physical presence of the mountains combined with the distance and climate limited travel between the East and West of the county a century or so ago much more than is the case in these more mobile times.

Below the mountains, nestling in the foothills, lies the other, lowland, half of Dunlavin parish. This area is centred on the village of Dunlavin itself. The village serves the area as a services centre, and dates from the late 17th century. Dunlavin is not mentioned in the Down Survey, and does not appear on the 1655 map. Two areas just outside the village – Rathsallagh and Fraynestowne - are marked in but the village itself was obviously not in existence in 1655 at all. This is obviously still the case in 1683, as Dunlavin does not appear on Petty’s map of county Wicklow from that year. Once again, some neighbouring areas( including Rathsalagh and fraynestowne) are marked in, but Dunlavin, itself is still conspicious by its absence.

The present town of Dunlavin was founded, therefore, some time after 1683. Lord Walter Fitzgerald tells us that the town dates from the late 17th century and owes its origins to the Bulkely family. This family came from Cheshire (via North Wales ) and in 1702 Heather Bulkely married James Worth – Tynte, thus beginning the long association of the Tynte family with Dunlavin. The village of Dunlavin may have been founded with the idea of its becoming an ivory tower of education, as the following extract written in 1709 shows : “ Dunlavin, a dirty village, but prettily situated on a hill belonging to Sir Richard Buckley[sic] who talked of establishing a university and building a college here; nay, went so far as to have the bricks burnt for this purpose, but I think that project is now at an end….”

While it did not become a university town, the village of Dunlavin, once established, seems to have grown quite quickly during the 18th century. It became a landlord village, built to Georgian architectural concepts. Some of these architectural concepts are still evident in the village – wide streets, a market square and a fairly uniform roof-line, for example. The most obvious sign of the improving spirit in 18th century Dunlavin was the building of a fine market house. This was erected in 1737 by Robert Tynte at a cost of 2,000, 1,700 of which was advanced by Tynte’s cousin Buckeley. Dunlavin market house was the scene of hangings on 24th May 1798, and it was from this building that thirty-six prisoners were taken to be executed on the fairgreen in Dunlavin on that same day.

As the 18th century gave way to the 19th the village of Dunlavin continued to grow. The census of 1821, the first real census of Ireland (however unreliable it might have been), shows us that the village of Dunlavin, which did not exist 150 years or so before, now had a population of 897 people, while the surrounding area supported even more people – 1,495 according to the census. The village was on one of the main roads to Wexford then – before 1829 the Tullow and Wexford road diverged at Blessington and went through Ballymore- Eustace, Dunlavin and Stratford-on- Slaney, before rejoining the present road again near Baltinglass.

Despite the loss of its main road status, the population fo the village continued to grow, and by the 1840s the population had reached the 1,000 mark. A Relief Commission letter, dated January 17th 1847 refers to “ Dunlavin , population 990 (a figure taken from the 1841 census), a comparatively good market town, the capital of a great district…. It is chiefly supplied from Naas.” This letter brings us to another aspect regarding the location of Dunlavin village. As we have already seen, East Wicklow wit its larger towns of Bray, Wicklow and Arklow was a world away from Dunlavin. However, though the village of Dunlavin lies within Co. Wicklow, it is only a mile from the Kildare border. This has numerous implications for life in the village. Even today Dunlaviners are much more likely to work in ( or move into) neighbouring Kildare than any other part of Co. Wicklow- including the Donard centered upland portion of Dunlavin parish itself. The lowland part of the parish, including Dunlavin village, has a hinterland that includes a large Co. Kildare percentage.

Thus we see that Dunlavin, founded in the late seventeenth century grew up as a landlord village on the Wicklow-Kildare border and had a population of about 1,000 people when the famine struck. However, all of this is by way of introduction and we now move on to the second variable in local history – time. This study begins in the 1880s and some idea of the post famine decline of the Dunlavin region may be gleaned from reading one of the first entries in the diary kept by Fr. Frederick Augustine Donovan, who became P.P of Dunlavin in 1884. Fr. Donovan wrote: “ The Roman Catholic parish of Dunlavin comprises the civil parishes of Dunlavin, Crehelp, Tober, Rathsallagh, Freynestown, Donaghmore and Donard. The total population of this parish, according to the statistics furnished by the census commissioners was as follows:

In 1841 - 9,599 people.

In 1881 - 4,386 people.

Obviously the village of Dunlavin was no longer the pre-famine boomtown of yore, but by the early 1880s some stabilisation of the post-famine decline had taken place. In 1881 the village, which had a population of 615 (down from 651 in the 1871 census) was included among the post towns of Ireland. Dunlavin post office was also listed as a telegraph office, a money order office and a savings bank. The village was also a market town and Wednesday was market day , while the fair days in Dunlavin were on 1st March, 10th May, 16th July, 21st August, 12th October and 30th November.

As a market town, Dunlavin served quite a large hinterland. We must remember that transportation was slower in 1881 than it is today, so the village of Dunlavin would have functioned as a higher order central place. Basically a central place, in geographical terms, is a place that serves an area larger than itself, and there is no doubt that a wide variety of goods and services was available in the village in 1881. In addition to basic lower order goods and services – grocery shops, public houses, R.I.C station, post office e.t.c – the village had all the hallmarks of a stable developed settlement. There was a resident doctor, George . E. Howes M.D., who had studied in Edinburgh. Petty sessions were held once a fortnight and the local magistrates were Joseph Pratt Tynte and Edward Pennefather of Rathsallagh House (an Oxford graduate). The clerk of the court was W.R Douglas.

As a village with a large hinterland and thus with a large catchment area of population, Dunlavin had its own national school. The national school is a symbol of the importance of any rural settlement, and there were six schools under Catholic management in the Dunlavin parish in the 1880s. Dunlavin village had both male and female nationals schools and there were mixed schools in Donard, Merginstown, Davidstown and Seskin. The master of the boys’ national school was Thomas Grace, while the girls school was under the charge of a Miss Toomey. There was also a protestant school in Dunlavin (with Charles O, Connor as master) in 1881.

The village of Dunlavin was also large enough to provide permanent banking facilities, a services which every community needs and values. The Munster Bank Ltd. Opened a new branch in Dunlavin in February 1874. The bank was described as “ a neat stone building” and in 1881 the manager was Robert Crilley. By 1890 this had changed to a branch of the Munster and Leinster Bank Ltd., open daily under the managership of A. Warmington. Nowadays the bank in Dunlavin is only open two days a week, which is probably an indicator of the villages decline as a central place, partly due to better and faster transport in the 20th Century.

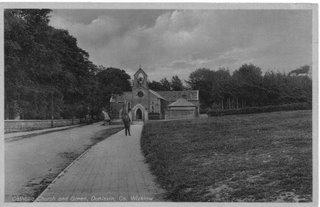

Dunlavin had two churches in 1881. The protestant church was described as “a neat, plain building with a square tower”, while the catholic building was “ a plain but large and commodious structure”. The prodestant minister was Rev. J.C. Carmichael, while the catholic parish priest, Canon James Whittle also held the Diaconal Prebend of Tassagard, again probably an indication of the status of Dunlavin parish (and village) at the time. Dunlavin village did not have the advantage of a railway station in 1881. This came in 1885 but even before the coming of the railway, a village like Dunlavin, which had enough shops and businesses to ensure keen competition between similar establishments, had links both within and beyond its hinterland. One businessman in Dunlavin in 1881 was Martin Kelly “ Grocer, Draper, Seedsman and Tallow Chandler”. I have in my possession a number of Kelly’s business documents, mainly dating from the 1870s, which show that Kelly traded with many Dublin firms, including Thomas Crotty, 57 William St., Keating and Moorhead, 17 Andrew St. and James Crotty, Hibernia Buildings, Victoria Quay. Dunlavin’s cross-border links to Co. Kildare meant that Kelly supplied candles to the army in the Curragh camp. Dunlavin'’ hinterland was indeed quite large!

Martin Kelly is only one of a number of businessmen who were making a living in Dunlavin in 1881. Slater’s directory for that year lists the shopkeepers, tradesmen, farmers and other “people of importance” in the village. The full extract from Slater’s directory can be read in Newbridge library.

The picture of Dunlavin in 1881 that emerges then is one of a multi – functional market town which served a large rural hinterland. The town supplied the surrounding area with tradesmen and craftsmen and with goods and services. The surrounding area in turn concentrated mainly on agriculture and brought its produce to the market in the town. In fact, later, Slater’s Directory for 1881 paints a picture of a community practically self sufficient in many trades and crafts. Nicholas Byrne was a sadler, as was Richard Fisher. John Mullally had a coach-building business while the Byrnes, John and Patrick, worked as a tailor and a shoemaker respectively. Samuel Rawson also made shoes, while Matthew Hanley and John kelly made nails – trades now extinct in Dunlavin.

The list in Slater’s directory goes on (see Newbridge library), but I do not intend to go through each individual entry here. The business people listed by Slater’s directory – shopkeepers, manufacturers, publicans, e.t.c - acted as brokers between Dunlavin and its hinterland, between the village and the wider world. Their need to buy supplies, raw materials e.t.c probably brought them into contact with people from beyond Dunlavin’s immediate hinterland quite often. Indeed, Martin Kelly’s business documents prove as much. As well as business people, the larger farmers like John Harrington, Thomas Molyneaux and James Norton would have had dealings beyond the immediate hinterland of the village. Both shopkeepers and farmers(or, at least, larger shopkeepers and larger farmers) have traditionally been seen as leading citizens within their own localities in rural Ireland, and leaders of the people too.

Certainly both farmers and shopkeepers, as they had links outside the area, would have been more likely to come into contact with new people and new ideas. Mainstream political ideas like land reform and Home Rule were probably introduced and nurtured in the Dunlavin area by these leading citizens. One organisation that aspired to both Home Rule and land reform was the National League, a branch of which was established in Dunlavin in the 1880’s.

A study of the names of those involved in the League is quite interesting. The local papers printed the names of the peole that attended League meetings, and certain names recur quite often. However, I think it is fair to say that larger farmers were much better represented than larger shopkeepers or business people in the Dunlavin branch of the National league. In fact, I think it is fair to say that while the National League lasted in Dunlavin(during the 1880’s), “ larger farmers monopolized control and the expression of opinion”. This would concur exactly with the findings of P.H Gulliver in relation to Thomastown, Co. Kilkenny. Names like Harrington, Molyneaux and Norton appear many a time and oft in the local press and it is quite obvious that the leading local farmers were deeply involved in the local politics and issues of the day.

Local shopkeepers, publicans and business people, on the other hand, are not as well represented in the pages of the local press. It would seem that they were not as deeply involved in local politics, and more particularly in the National League. Whether large shopkeepers were more conservative than large farmers, or whether they were simply not as interested in land reform, the avowed secondary aim of the National League(the league’s primary aim was Home Rule) is hard to gauge. As they did business with all shades of political opinion, perhaps it was harder for shopkeepers to be openly Nationalist. Would Martin Kelly have supplied candles to the army, for example, if the authorities on the Curragh saw him as a leading local nationalist?

While we will never know the answer to this question, there is no doubt that the lists in Slater’s Directory for 1881 show the existance of a resurgent Catholic middle class in Dunlavin which probably emerged in the post-famine decades. This is interesting, as Fr. John Francis Shearmen had noted that anti-catholic discrimination was the norn in Dunlavin during the 1860s. He writes about the evictions of catholic families in the Glen of Imaal, and goes on to say that “the district of Dunlavin has been scarcely more fortunate”. The evictions of Catholic tenants were not new in the area in the 1860s either. In the aftermath of the 1798 rebellion, William Ryves of Rathsallagh had evicted many catholic families. Father Shearman goes on to say that in Dunlavin village at the time of writing (1862), Catholics were “a proscribed race”. This would hardly indicate that there was a prosperous Catholic middle class in the village in the 1860s. Indeed, Shearman goes on to tell us that “Catholics in general few exceptions aren’t wealthy, being severely tried by the ordeal of the three past inclement seasons”. Apart from telling us that most Catholics were quite poor, this extract also shows that dependance on the weather was a feature of life in rural areas at this time. Bad weather could mean hunger, and bad weather was at least partly responsible for the agricultural depression of the 1870s and the founding of the Land League in 1879.

Despite Father Shearman’s observations regarding Catholics in the Dunlavin area in the 1860s, Slater’s directory for 1881 shows us that many Catholic were included in the middle class of business people and farmers. This could indicate a “Catholic recovery” during the 1860s and 1870s. It is also possible that Shearman , A Catholic curate in Dunlavin painted a deliberately bleak picture in his writings, but as they were not intended for publication, I think this is quite unlikely. Whatever the reason, the fact remains that there was a fairly small but prosperous Catholic middle class within the population of Dunlavin by 1881.

Mention of population brings us on to the third variable in local history – people. What makes the third variable so interesting is their behaviour and in recreating the past the local historian must become a story-teller as well. Anecdotal evidence is vital – but of course must be put into context if possible. One anecdote about the Dunlavin area at this time concerns the collection of the poor law rate.

Dunlavin was in Baltinglass poor law union district and in 1890 a local scandal erupted. The man at the centre of the scandal was from Crehelp townland. He was the collector for the Dunlavin area and he managed to misappropriate between one hundred and twenty and one hundred and thirty pounds of the ratepayers’ money. He even collected the rates before they had actually been struck in most cases. The Board of Guardians prosecuted this man, who would have been liable to pay three times the amount that he had embezzled and serve a prison sentence had he been found guilty. However, he was actually acquitted at Dunlavin Petty Sessions, so the guardians brought the collector’s case before the Baltinglass Quarter Sessions. However, the situation had changed before the man appeared at Baltinglass.

There had been a delay with serving him with the appropriate “civil bill”, so he had had time to sign over his farm and all his possessions to his wife and son. When his case came up, he was declared a bankrupt and his promissory notes could not be honoured. His guarantors had to try to pay up and one of them was financially ruined by having to do so. Even with the guarantors monies paid up, there was still over one hundred pounds outstanding in May 1890.

One of the most interesting things about the rate collector’s episode was the way that it was reported in the “Leinster Leader” at the time. The “Leader” was founded in 1880 as a rival to the unionist newspaper “The Kildare Observer’. Thus the “Leader” had a Nationalist agenda, and was looked on with suspicion by the authorities during the 1880s and 1890s , when the land reform and the Home Rule movements were very strong. Indeed, in the same year as the rate collector’s episode happened the “Leader” speaks of a campaign of vengeance against our staff. Four printers had been imprisoned, a reporter ad been arrested and the proprietors of the newspaper had only recently got out of jail(in poorer health than when he was arrested).

Given the nationalist aspirations of the “Leinster Leader”, it was only natural that they should make hay over the rate collection affair. In 1890, the Baltinglass Board of guardians was predominately protestant and unionist. The collector was a protestant and the “Leader” states that his brethren on the board simply allowed him to do what he liked until the day of reckoning came”. The collector’s acquittal at Dunlavin petty sessions is described thus: “This man was brought before that congenial court, the Dunlavin petty sessions and allowed to go scot free”. In fact, the “Leader” tells us that “The doings of the Tory deadheads who rule the roost in Baltinglass often afford interesting reading on the law as it is administered by them, but for a paralell to the case [of the ex-collector of rates], Ireland would be searched in vain.”

The “Leinster Leader”, then , reported the rates debacle with glee, butsuch an approach was only only to be expected from a newspaper whose weekly column about the events in Westminster was entitled “In the Enemy’s Camp”! There is no doubt, of course, that unionists did control Baltinglass Poor Law Union in 1890. Joseph Pratt-Tynte, the mani landlord around Dunlavin village, was an ex-officio member of the board. While he may not have attended many meetings (two in 1889 as against sixteen attended by Edward Fay, the local elected Dunlavin representative on the board), Tynte’s ex-officio status on the board was never threatened. Tynte had 2,532 acres in Co. Wicklow with a gross annual valuation of two thousand one hundred and eighty six in 1883, while other holdings in counties Dublin , Cork, Kilkenny and Leitrim brought his total estate to 5,013 acres with a valuation of four thousand six hundred and seventy seven pounds.

Fay, on the other hand, was a member of a leading Catholic family in Dunlavin. The post-famine era saw the emergence of an admittedly small but steadily growing, Catholic middle class in the village. In the 1860s the Fays were among the nine leading Catholic families in Dunlavin village. The leading Catholic family , the harringtons, had a valuation of one hundred and thirty six pounds and ten schillings. Obviously, the gulf between the protestant landlord class and the Catholic middle class was wide in late nineteenth century Dunlavin. Edward Fay, a butcher and spirit dealer, was elected as Poor Law Guardian in March 1888. He was the first Catholic to represent Dunlavin in this position. However, it must be said that Fay was one of only a few shopkeepers who seemed to be involved in local politics, which was more the domain of strong tenant farmers, as already noted.

Strong tenant farmers, in their turn were well below the local landlords on the social ladder. Joseph Pratt Tynte, who was born in 1815 and married to Geraldine Northey of Cheltenham in 1840 was a resident landlord living at Tynte Park House, about two miles from Dunlavin village. Tynte was also a local magistrate and landlord control in Dunlavin was quite strong. There is no evidence of a small clique or cartel of local landowners below Tynte, despite some subletting by strong tenant farmers, a practice which went back at least as far as the mid 19th century.

Tynte, of course, was a leading figure in Dunlavin Church of Ireland circles. Indeed, he is buried in the local Church of Ireland cemetry. In 1881, protestants made up 21% of the population of Dunlavin parish. Protestant children were better educated (or at least more literate) than Catholic children in Dunlavin at this time, indicating that protestants generally were not to be found in the lower social strata of the area. Both a Catholic parish priest (Frederick Augustine Donovan ) and a protestant rector(Samuel Russel McGee) have left unique written records of their time in Dunlavin.

Donovan served there from 1884 to 1896, while McGee was in Dunlavin from !894 to 1905. McGee’s account of his time was published retrospectively in 1935 but Donovan’s diary was never published, though it has survived through the last 100 years or so. Both documents provide a wonderful insight into the ecclesiastical life of Dunlavin during the study period. The late 19th century was a period of change and consolidation for both the Catholic church – in the wake of the post-famine “devotional revolution” – and the protestant church – in the wake of the 1869 Disestablishment Act.